Formed in 1906, the Jolly Entertainers were a children's band composed of five girls and two boys, six of them orphans. Their music teacher, Herman Draper, quit his job as superintendent of an orphanage to pursue an idea: a home in which children would fend for themselves, refusing charity and eschewing government intervention. The home would be funded by the children's own efforts, as they toured the nation giving concerts in every city and town along the way. It was a foolhardy dream, bound to fail. Or was it?

Herman Mainard Draper was born in Rainham Centre, Ontario, Canada, in 1856. He was the son of a preacher, and had eight brothers and sisters. The family moved to nearby Welland, Ontario, and later to Battle Creek, Michigan. He was a student at Battle Creek Academy, and taught piano. He studied at the Boston Conservatory of Music, and also earned a certificate from the Tonic Sol-Fa College in London, England. Tonic Sol-fa was a simplified method for teaching sight-singing.

On September 18, 1878, Draper married 20-year-old Annie Pacey of Port Stanley, Ontario, and they had two sons: Harry, born 1880 in Battle Creek; and Cecil, born 1882 in London, Ontario, where the Draper's had taken their vows and where Herman was now teaching Tonic Sol-fa. He also held a class in nearby St Thomas.

Shortly after the birth of Cecil the Drapers moved to Lincoln, Nebraska, where Draper had a job waiting for him at the University of Nebraska's Conservatory of Music. Draper explained his program in the university's catalogue for the fall term of 1882: "Instruction will include the study of registers, solfeggi, scales and arpeggios; of the different styles of singing; and of English and Italian songs. In the elementary and chorus classes of this department will be introduced the popular Tonic Sol-fa System, which is justified by its great success in England and elsewhere, and the apparent demand for it in this country."

"Apparent", indeed. Tonic Sol-fa had its opponents, some of them among the faculty. Draper's pupils, they contended, would never be able to read standard notation and participate in a conventional orchestra, and thus their education offered little prospect for a career in singing.

Within weeks of the start of the term Draper gave a demonstration of his system, but he won no converts among the skeptics. Early in 1883 S. B. Hohmann, Director of the Conservatory of Music, hired another teacher, Louise Seacord, "a thorough musician and superior vocalist". Draper refused to be ousted, and on June 15 he was somehow appointed the new director of the Conservatory. The minutes of the Board of Regents read: "Resolved, that Prof. Wm. M. Draper [sic] be hereby appointed Director of the Musical Conservatory without salary and that the appointment of S. B. Hohman heretofore made be annulled. Adopted." On July 10, his position was confirmed, but Draper's victory was short-lived, as only an hour later the decision was reversed: "Resolved, that the application of Wm. M. Draper for appointment as Director of Conservatory of Music be indefinitely postponed, and that Mr S. B. Hohmann be continued as such Musical Director upon the same terms as heretofore..."

Draper left, but he wasn't about to give up on Tonic Sol-fa. He gave lessons at local public schools and churches, and placed ads in newspapers. He taught at St Claire Hall, the fall term beginning September 17, 1883. On the 2nd day of the 18th annual meeting of the Nebraska State Teachers' Association, held March 25-27, 1884, Draper gave a performance: "In the afternoon, Prof. Draper, with his class of girls, presented a vocal drill in the Tonic Sol-fa system, which was very admirable." The March 28 edition of the State Journal reported that his "class of 16 girls, ranging in years from 10 to 14, did some excellent work, which spoke louder than words of the superiority of the Tonic Sol-fa system as a teaching medium. The time being restricted to half an hour, his program was of necessity limited, but during the exercises the whole audience of about 300 teachers seemed deeply interested." He was garnering acceptance for Tonic Sol-fa, and for the next two years Draper gave demonstrations and lessons in nearby towns, including Seward. Impressed, the school board of Seward asked him to teach there.

The Drapers moved to Seward in 1887, but not for long. They went on to Kearney, Nebraska early in 1889, where Draper taught Sol-fa at local schools and put together the Kearney Juvenile Band. Wherever he went, Herman was successful with his musical method: "It has no lines, no spaces, no clefs, no sharps, no flats, no naturals, no time figures, nothing but music in a plain, practicable, sensible notation as simple and natural as the music itself. Children comprehend and enjoy it and can learn to sing by it as readily and as well as they learn to read from books."

In 1889 it was reported in the Kearney Daily Hub that Draper was "giving extreme satisfaction with his vocal methods of teaching music by the Tonic Sol-fa system in the public schools of this city. The pupils receive certificates for their ability in 'musical memory, singing in time, singing from the modulator, and in ear exercises.' The professor has over a thousand pupils undergoing instruction of whose progress a record is kept."

He also opened Draper's Music Store, and issued a catalogue for his growing stock of sheet music. He sold instructional books and violin strings, and offered lessons in "piano, violin, guitar and any other instrument..."

Annie Draper's sister, Edith, died of apoplexy in 1894. She and Herman took in her little girl, also named Edith.

|

| 1890s: Herman and Annie Draper, with their two sons Harry and Cecil, and adopted niece, Edith |

The Kearney Normal School, Business College, and Conservatory of Music opened its doors for the first time to a mere 50 pupils on September 10, 1895, and Draper, one of the school's incorporators, taught there for some time.

In the late 1890s, the Drapers moved to Calumet, Michigan, in the Upper Peninsula, where Herman opened a new music store and taught voice and various instruments.

During an extended vacation in 1900, he visited Burley, a socialist colony in Washington, established only two years earlier by the Co-Operative Brotherhood. At that time the colony had a population of 45 men, 25 women, and 45 children. Draper arrived in May and remained as a guest. He had already brought two horns with him, and sent back home for more. Additionally, he borrowed and rented other instruments and formed a children's band, composed of 24 girls and boys. That summer they journeyed to Tacoma and on to Seattle, where a concert was given August 21 at Ranke's hall. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported ahead of the event that the band "has already achieved a good reputation. An extensive programme has been prepared, consisting of vocal and instrumental selections. The latter will comprise both band and string music and some fine choruses are included in the vocal numbers." A fall tour of Oregon resulted in a loss of money, and Draper returned to Calumet. Without their leader, the children's band lapsed into oblivion.

But Draper's interest in socialism continued, and he read magazine's like Burley's own Co-Operator, and Wilshire's, whose publication offices moved to Toronto after the magazine was banned in New York.

Draper organised the Twentieth Century Mandolin and Guitar Club in Calumet, and within two years its membership grew to 75 kids from 8 to 14 years old. The club had two pianos, one organ, and some fifty violins, mandolins, guitars and brass instruments, as well as stacks of sheet music and instructional books.

Draper formed a brass band with 18 of the children, and in 1903 he came up with the idea of occasionally utilising the band to raise money for his new goal: establishing a home for children (patterned somewhat after Burley's cooperative model) in which the little orphans would fend for themselves by giving concerts. He also wanted to raise money for a vehicle that could transport his band. The Co-Operator reported that "Brother Draper is putting all he has -- his love, his time, his talent and his money -- into this work, and he calls on all interested to correspond with him..."

But Draper's efforts must have failed to raise sufficient funds, for it was in 1903 that he accepted an offer "to take temporary charge of a home-finding association supported by charity", the Good Will Farm, a shelter for homeless kids. "I expected they would be able to secure a superintendent within a few weeks, but the board of directors decided they had found one in me, so I stayed on the job for three years."

There were only a handful of children at the Good Will Farm, though that number would quickly grow. It was an actual farm, located three miles outside of Houghton, not far from Calumet.

|

| Vintage postcard. The photo was also used for a 1905 newspaper article on Draper and the Good Will Farm. |

In 1903 a new home was built on the property, which Draper described in an interview two years later: "This is a frame building on a stone foundation and consists of a basement, which is used almost exclusively as a playroom for the children...Here they also have five swings, and one wall is almost covered with band instruments, which are at the disposal of any boy or girl who takes enough interest in music to make use of them, and there is scarcely an hour in the day that some one is not tooting."

The first floor held the Drapers' private quarters, as well as a school room, dining room and pantry. "The second floor is divided into girls' dormitory, girls' toilet and bathroom, nurseries, sewing room and bedrooms for the help." Above that was the boys' dormitory. Draper was quick to say that the house was "thoroughly up to date", though the grounds needed some improvement. In 1904 they converted a portion of the property into a "lovely little park on the beautiful shores of Portage Lake." The park had swings, merry-go-rounds, seats, picnic tables and a bonfire pit. There was also a barn and stable, where they kept five cows, two calves and three horses.

Another important feature was the printing press, which Draper taught the children to use: "...we set the type and do the press work for Good Will. With this we are not only disseminating the news of the work being carried on at Good Will Farm to our thousands of patrons, but we are giving our girls and boys the foundation, if not teaching them outright, for one of the most useful trades possible for them to learn."

The Duluth Evening Herald reported that the farm "is supported by contributions from charitably inclined people. Mr. Draper has organised a band among the children, and they have been giving concerts in several cities in this part of the country for the benefit of the home." The band performed in numerous cities throughout the Upper Peninsula, and their first tour allowed Draper to pay off $500 of $3000 owed on the new house. Newspapers gave glowing reviews of successful concerts, and they were much in demand. The band left July 1, 1906 for a 10-day tour that would prove to be their last.

|

| Photo of the Good Will Farm during winter. |

Even before officially leaving his post in mid-August Draper had already reconsidered his plan to start a home in Seattle. Part of his negotiations with the Good Will Farm was that he be allowed to take the children with him, and this request was granted. There were twenty-one children, aged 8 to 16, in his personal care. What he needed now was a vehicle large enough to transport such a large group, and in July of 1906 he made an excursion down to Detroit to inquire about having such a vehicle built. George F. Strong, whom Draper had met in Houghton, was hired for the job. A trade magazine reported in November, "The chassis is being built by the Rapid Motor Vehicle Company, of Pontiac, Michigan. The machine will have 24 horsepower, with an 18-foot wheelbase and 21-foot frame, and will be capable of making 16 miles an hour."

The Rapid Motor Vehicle Company specialised in building trucks and were known for their Pullman Passenger cars, capable of seating 12 people. The work, which was actually being done in Detroit, was progressing rapidly, as detailed in Automobile Topics magazine: "The car in general outward appearance resembles a street car, having vestibuled ends. It is 26 feet long, 7 feet 6 inches wide and 7 feet high inside. Beneath the seats, which extend along both sides, are lockers for bedding and clothing. At night the car can be converted into a sleeper by means of iron rods strung across the interior, upon which the cushions will be placed, thus providing two tiers of mattresses." Upon completion the car seated 22, and was said to be "the only car of its kind in the country", for which Draper paid $3000, the last of his money.

But something had gone terribly wrong. Draper was forced to restore the children in his care to the Good Will Farm, which must have been heart-wrenching. Draper convinced the home to make a few exceptions, as he couldn't bear to see families broken up, as they often were. Ultimately, a much reduced party would make the pilgrimage west. The children included Herman and Annie's own daughter, Birdie, as well as Italian siblings Mike and Maggie, and four Norwegian brothers and sisters, Hartel, Doloros, Gudrun and Phillis, all from the Good Will Farm. Postcards were printed to advertise their intentions, showing Draper and the children with their various instruments. This new band of juvenile musicians was called the Jolly Entertainers.

|

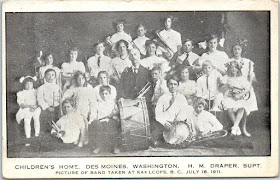

| Though this card was printed after they moved to Des Moines, Washington in 1908, the photo is of the original line-up of the Jolly Entertainers, probably taken in 1906. Below: the back of the card. |

Wasting no time, the Jolly Entertainers made a tour of Michigan and Wisconsin while the vehicle was still in production. Draper and his band left Houghton for the last time on October 31, 1906, and headed for Detroit. Accompanying them were Annie and her sister, Louise McKay ("Aunt Lou"), as well as George Strong, who apparently volunteered to drive the vehicle. Draper had already sent furniture and other belongings to Seattle by freight.

Draper could have had the vehicle delivered to Houghton and taken a more direct route through Wisconsin, but to avoid nigh impassable roads and harsh winters it was decided they'd go down to Indiana and head west from there. Their first stop was in Jackson, Michigan, where the car was shortened by six feet. The original length was intended to accommodate twenty-one children, but now there were only seven, so the vehicle was impractical. Travel was slower than expected. The top speed of 16 mph was contingent on good road conditions.

They stopped in Elkhart, Indiana, then Goshen, giving concerts. Their peculiar vehicle attracted attention wherever they went. Trouble began just after Christmas: following a brief stay in Kokomo, they headed south for Tipton, but were forced to turn back, their vehicle breaking down on a farm road four miles south of Kokomo. A farmer fed the hungry group, then hauled the vehicle into his barn. After a phone call to Kokomo, the town officials decided it was best to send the children to White's Manual Labor Institute just outside of Wabash, until Michigan authorities could figure out what to do with them. White's Institute was intended to educate and train troubled and difficult children, and Draper's wards clearly didn't belong there, but it would be many weeks before they were released into his custody.

|

| Postcard, 1906, letting folks know that the Drapers, as well as the Jolly Entertainers, are moving to Seattle. |

In the meantime, Draper and Strong were feuding. Strong was owed money for driving, as well as for repairing the vehicle, which he insisted be paid before continuing the journey to Washington. At one point, Draper tried to sell the vehicle, but no one else had use for such an odd contraption. The band played April 10 in Elwood, south east of Kokomo, but went by train. Fortunately, Draper and Strong were able to settle their differences, and the trip resumed in mid-April.

The spring weather being much more agreeable, they headed north through Illinois. At every stop they made the Jolly Entertainers played on street corners and sold postcards to stir up interest in their concerts. The little troupe explained their mission and the postcards sold quickly. The publicity worked, and the kids rarely played to a house that wasn't filled to capacity. As well, Draper always made sure the local papers knew they were in town, and reviews were invariably positive. En route their act had developed from an instrumental and choral concert into vaudeville, by including dance, comedy skits, plays and poetry recitals.

They spent the entire month of August in western Montana, playing extended engagements at theatres in Missoula, Sanders County, and Havre. As the roads proved too muddy and treacherous for their vehicle, Draper had it loaded onto a flatbed rail car and shipped to Seattle. The party also took the train, but stayed for a week in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho for a number of performances in September.

Draper's goal from the beginning was to reach Seattle by September, so that the children could start the school year on time, but they didn't arrive until October. They found a temporary abode in Ballard, which was annexed by Seattle only a few months earlier. The trip had been an ordeal, but wholly necessary. Said Draper, "[A]ll of us have the satisfaction of knowing that each worked his or her own way to the promised land."

|

| The Jolly Entertainers while still in Ballard, 1907 or 1908. The 7 original members have been joined by a growing mob of little musicians. |

The first telephone lines in Des Moines were put up in 1908, provided by the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company; otherwise, the town was still in its primitive stages. There was little, if any, electricity. There was no running water -- residents had to pump their own. Outhouses were common, as there were no sewers. The privileged owned a septic tank. There was no highway in or out of Des Moines until 1916, only a wagon-wheel trail. The most popular form of transportation was the "mosquito fleet", the myriad steamers which plied the waters of Puget Sound, connecting communities.

|

| View of Des Moines, looking west. At right the Hiatt hotel can be seen; it became the Children's Industrial Home for the next two decades. |

Draper stated in an interview, "Within our home everybody helps every one else. Housework, simple gardening, and the cultivation of a social instinct which sees the needs of others offers cheery aid, are the domestic studies ceaselessly pursued. Wholesome food, warm clothing, comfortable beds and clean quarters, plenty of sleep and air and play, with a good season of work, combine to make every member self-respecting, responsible, level-headed, and -- best of all -- level-eyed, as shown by the independent look of equality with which our children approach the world when they give to it the very best of what they have in return for what they actually need."

|

| Postcard, from a photo taken September 11, 1909. No opportunity wasted, the drum reads "Pictures of the children & home 5 cents each". |

|

| Early photo, date unknown. |

Draper also taught the boys how to repair cars and trucks. The girls learned how to sew and knit.

The Jolly Entertainers travelled in a caravan of trucks, with "Daddy" and "Mother", and usually with one or two teachers in tow. The children brought their school books. They also brought their toys, said Draper: "They are ever anxious to romp and play with the children they meet in the towns and cities, and the dollies and trinkets must go with them on their little journeys." Wherever they went on their tours, the Drapers were always able to find overnight lodging for the children. This usually wasn't a problem, for, if there weren't enough hotel rooms available, the good citizens of the community would take in three or four at a time. As one newspaper put it, "Instead of finding it difficult to place the children there were not enough in the party to go around." Where possible they camped out in tourist parks or municipal parks.

|

| Rare view of the Jolly Entertainers in performance. Date unknown, but early in their career. |

The children attended public school in Des Moines, and the entertainment provided by the Jolly Entertainers was secular. Draper said, "I do not cram religion down the children's throats. We try to live the Sermon on the Mount. Each morning we sing a few gospel songs, read a few verses in the Bible..." But he didn't teach them to turn the other cheek: "Frequently town children pick on our boys. I say to my boys, 'No one but a coward picks a fight. I never want you to strike the first blow, but I want you always to strike the last one.'"

|

| Folded card, 1912. Draper's manifesto. |

Their concerts were successful, if not financially, at least critically. Attendance was good, and often houses were packed, always to appreciative audiences, as the many newspaper reports attest. An excerpt from a 1911 newspaper article describes in some detail one of their earlier shows:

The program was a continuous play and was pronounced the best ever given by these little folks.

The first was a scene on the street. A bunch of children on their way to a picnic are met by Uncle Josh, who is persuaded to go along. They are followed by Happy Hooligan and Gloomy Gus, who also go to the picnic and get "filled up."

Scene 2 is the picnic full blast, children swinging, skipping, playing ball, boxing, etc. Uncle Josh is there, according to agreement, gets dumped out of the swings and has a general good time. Happy and Gloomy are the biggest toads in the puddle and the only break in the festivities is the appearance of a cop who attempts to arrest Happy, but the tables turned on him. Scene 3 finds a host of people buying tickets for the "big show". Scene 4 is the big show, given by the Lilliputians and it certainly is a "Big Show". This part of the program is made up of the most catchy songs, beautiful motions and poses, marches, graceful dances and the most laughable vaudeville ever presented on a Port Townsend stage by young performers.

The company will remain over and give another program tonight with an entire change of bill.

The price for the evening show was 35 cents general admission, 50 cents for reserved seats, and 15 cents for children under 14. Draper said he paid "from five dollars to one hundred fifty dollars rent for a theatre, depending on the size of the town."

No venue left untrodden, they even performed for a Washington chain gang in 1910. The children met them at the gate upon their return from work.

|

| Summer, 1910. |

|

| Draper didn't forget his roots. The Jolly Entertainers often toured Canada, mostly the Western Provinces. |

Later that year they had to cancel two shows in Moscow, Idaho. According to Draper, "the probate officer and prosecuting attorney had evidently come in contact with some old fossil, who wanted to become conspicuous as being interested in the welfare of children, so they interpreted the child labour law so closely that they would not allow us to perform in the theatre or even play on the street..."

Busybodies like these were annoyances that Draper had to deal with now and then, along with the occasional police officer upholding a by-law preventing the children from performing in the street.

|

| Folded postcard; this vehicle was probably used for local jaunts. |

|

| Newspaper ad from February 23, 1914. |

Sometimes the route was downright treacherous: "The bends in the road at times were so abrupt that our huge trucks were often obliged to move back and forth three or four times before making the turns, at other times they would be scraping rocks on one side, with the mountains extending hundreds of feet above them, while on the opposite side the wheels would ride within a foot or two of the edge, overlooking a steep precipice or a yawning abyss below..."

|

| A photo taken during their gruelling 1914 tour of California. |

They spent ten months in California, and "performed in 121 different towns and cities, in many of the finest theatres and opera houses of the state. Entertained the students of over 200 high schools and grammar schools, two state normals, two insane asylums, two state prisons, visited the great oil fields and wells at Coalinga, the gold fields at Oroville, the San Francisco world famous Golden Gate park, the seal rocks, Cliff house, ostrich farms, entertained in the Palace hotel, were invited as guests to theatres, spent a whole evening in Chinatown..."

|

| Draper was a member of the Elks. |

The Commission's investigation of Draper's Home was less than thorough: they simply wired the editor of Welfare Magazine in Seattle. The reply was terse, of course: "Institution without trustees or equivalent; several prominent men at first approved withdrew several years ago. Children no good training; taken out as entertainers. Property in Draper's name. Now acquiring additional place. Washington Labour Commission tried to suppress bill but found institution legal."

The Commission concluded that Draper was exploiting the children for his own profit. When he reached Los Angeles and applied for a permit to perform there they were refused, as it violated the State Child-Labour Law, which prohibited children under the age of 12 from providing entertainment. Despite the refusal, Draper made arrangements at a theatre to have the band perform. He and Annie were arrested that evening, and Draper was given a sentence of 180 days in jail and a $250 fine. The trucks and all the scenery and equipment were seized.

The next day a meeting was held. Present were representatives of the State Board of Charities, the Los Angeles Humane Society for Children, and the National Child Labour Committee, as well as the Drapers, the children, and their teachers. A proposition was made by which Draper could be set free. The agreement read:

We, the undersigned, hereby give you our solemn promise not to give any more performances in the State of California or en route, and to return immediately and directly with the children under out control to Des Moines, Washington, and we further promise that as long as these children are under our control or that we conduct our institution, that we will not give any public performances except those authorised by the Central Council of Social Agencies of Seattle, and that we will at once incorporate our institution as a Children's Home, to be maintained and conducted as such according to the laws of the State of Washington and the recommendations of the Central Council of Social Agencies, Seattle.

It was signed by Herman and Annie, and arrangements were made to send them back to Seattle by boat. Draper violated his parole by stopping in Oakland to secure a pardon from the Governor. It wasn't granted. Once they were back in Washington, beyond the reach of California authorities, it was business as usual for the Jolly Entertainers.

Money was never solicited, but Draper said he wouldn't refuse a "friendly donation". A 1920 flyer sent round to labour unions asked that each member contribute one penny to the home: "It certainly seems small, but think what it means to those children!" But he stopped short of calling it charity: "Oh, no! These kiddies print 'Good Will,' and for each dollar sent as per capita on the one-cent basis they will send a copy of their little paper, which should be passed around at your next union meeting, so that as many members as possible may read it and pass it on to others."

When the children grew up, they left the home, but a few stayed on. By 1914 two of the original seven Jolly Entertainers were old enough to assist Draper in teaching the children. Later, a fellow named Lloyd Sawner became the stage manager for the Jolly Entertainers, arranging lights and special effects for the shows. Julia James, nine years at the home, became a band leader, helping to rehearse the kids.

|

| Above and below: Post card dated Christmas 1913 showing the "Juvenile Quartet", a sort of act within an act. |

All day long a large steamer plyed the waters between Seattle and Des Moines loaded with capacity crowds. A continuous stream of autos of every description came over the new brick highway. The big dancing pavillion with accomodations for 1000 people was one busy whirl of happy dancers and in the beautiful park owned by the Children's Home were over 10,000 Elks and their families seated at tables and lunching on the hillsides and on either side of the beautiful little stream that runs through the park. The Elks and Marine band gave some fine concerts under the trees, and of course Daddy Draper's kiddies gave quite a program of solos, choruses and band numbers.

On October 31, 1921, courtesy of the Seattle Star newspaper, the kids of the Draper home, Mother Ryther's home, the Theodora home, and the Washington Children's home were treated to an afternoon screening of Mary Pickford in "Little Lord Fauntleroy", based on the children's novel by Frances Hodgson Burnett. All 150 of the excited kids piled into the Coliseum's balcony seats. Buses to transport them were paid for by local businesses. Two days later Draper's kids and the children from Mother Ryther's were treated to a special performance at the Colonial theatre by Jack Hoxie, a star of western films. Formerly in Wild West shows, he no doubt thrilled the youngsters with his roping expertise.

|

| Their new Ford "Pullman", 1923. |

|

| Draper, with Baby Edna, performing in the street, c. 1922. |

|

| The Jolly Entertainers stayed in Florida during the cold months of 1924/1925. Below: The back of the card. Baby Edna's presence drew larger audiences. |

The Jolly Entertainers were able to support their Des Moines home for 19 years, but on April 13, 1927 Annie died suddenly from heart failure. Her funeral was held four days later, without Herman, who had suffered a stroke earlier that morning. He had a second stroke the next night, April 18, and died at home at the age of 70.

|

| The Jolly Entertainers, circa 1922. |

Unfortunately, the home couldn't be maintained without the guidance, inspiration and management of "Mother" and "Daddy" Draper, and so the Children's Industrial Home was closed, and the hotel eventually demolished.

But the children were always determined never to sink into historical oblivion. The Harrington Opera house, built in 1904 in the tiny town of Harrington, Washington, was bought and restored in recent years, except for the walls of the dressing rooms, which were left untouched, a relic of the past. The children were only too happy to deface the walls with their signatures, and "The Jolly Entertainers, Sept. 18-19, 1916" is visible, along with other such scribblings for each time they performed there. Way to go, kids!